|

|

|

|

|

Back to 2016 Annual Meeting

Impact Of Observer Cultural Background On The Visual Processing Of Cleft Lip And Other Forms Of Facial Difference

Thanapoom Boonipat, BS1, Oliver Darwish2, Tiffany Brazile, BA1, Philip Montana, BA1, Kevin Fleming, PhD3, Mitchell Stotland, MD4.

1Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH, USA, 2Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA, 3Norwich University, Norwich, VT, USA, 4Sidra Medical Center, Doha, Qatar.

Background:

Facial difference affects quality of life, and evidence suggests that social bias and stigmatization often persist even after the provision of appropriate facial reconstruction1. In order to investigate the impact of observer cultural background on the visual processing of cleft lip and other facial deformities, we employed eye-tracking technology2,3.

Purpose:

To measure the impact of culture on observer eye-tracking patterns of faces with cleft lip and other deformities. This information may better inform surgeons’ conversations with their patients by improving understanding of how faces are reflexively interpreted by others. This knowledge may also help focus surgical reconstructive priorities.

Methods:

59 experimental and 59 control facial images were obtained from the senior author’s practice. Experimental images included the following diagnoses (15 cleft lip, 15 facial aging, 12 ear deformity, 7 facial lesion, 6 HIV lipodystrophy, 3 facial asymmetry, 2 nasal deformity).

Twenty standardized lookzone regions were mapped onto each facial image.

170 adult subject observers were recruited in two locations (107 in USA and 63 in Thailand) and asked to observe a slideshow of images while a digital infrared eye-tracking camera continuously recorded their eye movements.

Outcomes Measured:

The total number of eye fixations within the different lookzone regions was recorded. Factorial ANOVA analysis was performed to determine significance of gaze pattern differences between groups.

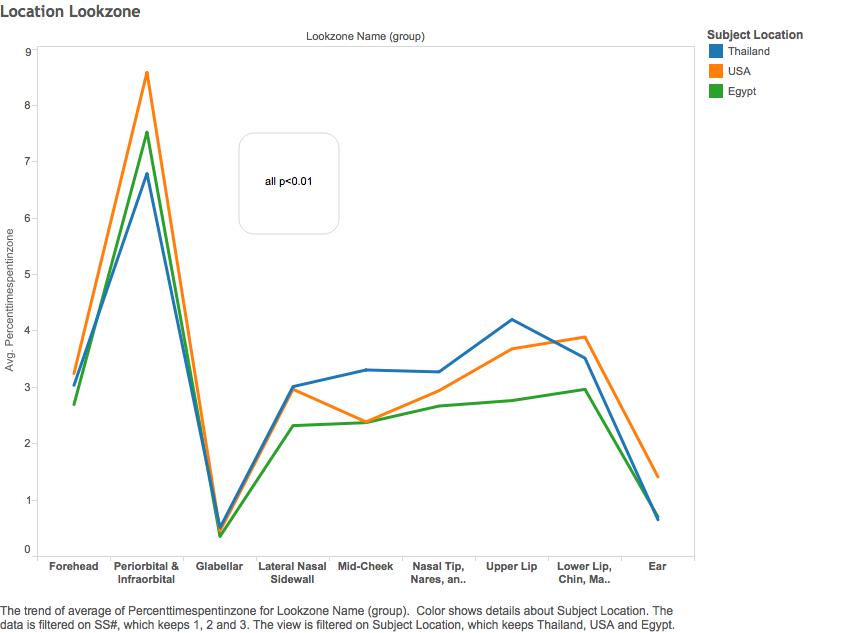

Results. The following observations were statistically significant at p<0.01 level. Compared to when looking at age-matched control images:

(i)

subjects in both Thailand and the USA preferentially fixated on the periorbital regions of the face

(ii)

Thai subjects fixated relatively more on lower facial regions while American subjects fixated preferentially on upper facial regions

(iii)

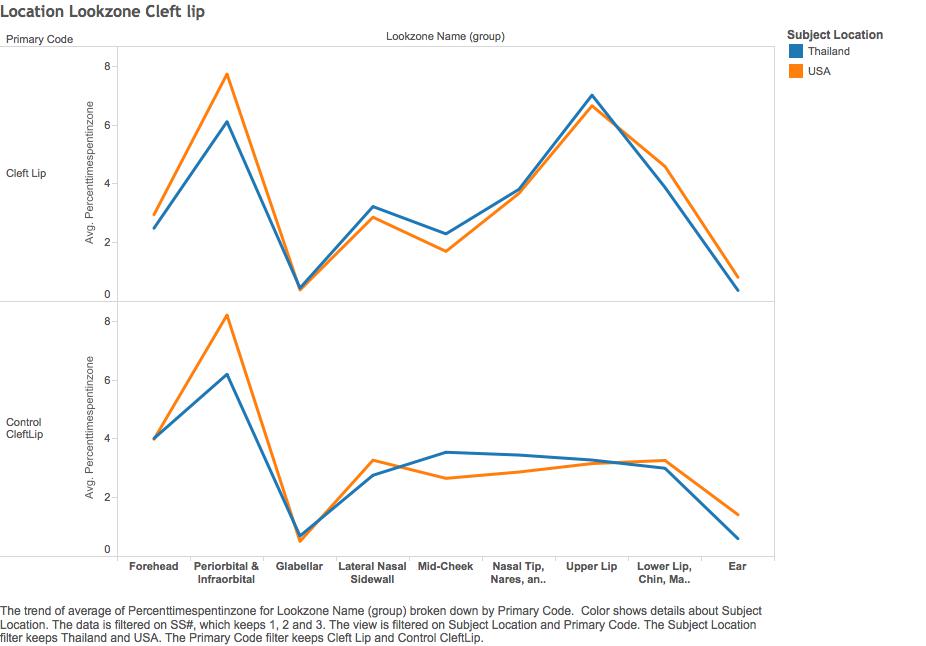

Both Thai and the USA subjects paid significantly greater attention to the regions of the affected upper and lower lip of images with cleft deformity, and the auricular region of images with ear deformity.

(iv)

Within this sample, statistically significant differences in gaze pattern were not detected for the other facial deformities considered.

Conclusions:

Western and Southeast Asian populations preferentially inspect the periorbital region during early visual processing of a face, and are similarly drawn to regions of difference

when observing cleft lip or ear deformity. Southeast Asians focus greater attention on the lower facial region while Westerners focus more on the upper/periorbital facial region.

References:

1. Berger Z, Dalton L. Coping with a cleft: Psychosocial adjustment of adolescents with a cleft lip and palate and their parents. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 48:435–443 Dec 2009

2. Blais C, Jack RE, Scheepers C, Fiset D, Caldara R Culture Shapes How We Look at Faces. PLoS ONE 3(8): e3022 2008

3. Eyetellect GazeTracker™, Charlottesville, VA. EyeTech Digital System, Mesa, AZ.

Back to 2016 Annual Meeting

|

|