Virtual Sub-Internships: Successes and Lessons Learned from Three Institutional Experiences

Meera Reghunathan, MD1, Paige K. Dekker, BA2, Kevin G. Kim, BS2, Kenneth L. Fan, MD2, David A. Brown, MD, PhD3, Amanda Gosman, MD1, Samuel Lance, MD1

1Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic Surgery, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, 2Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC, 3Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC

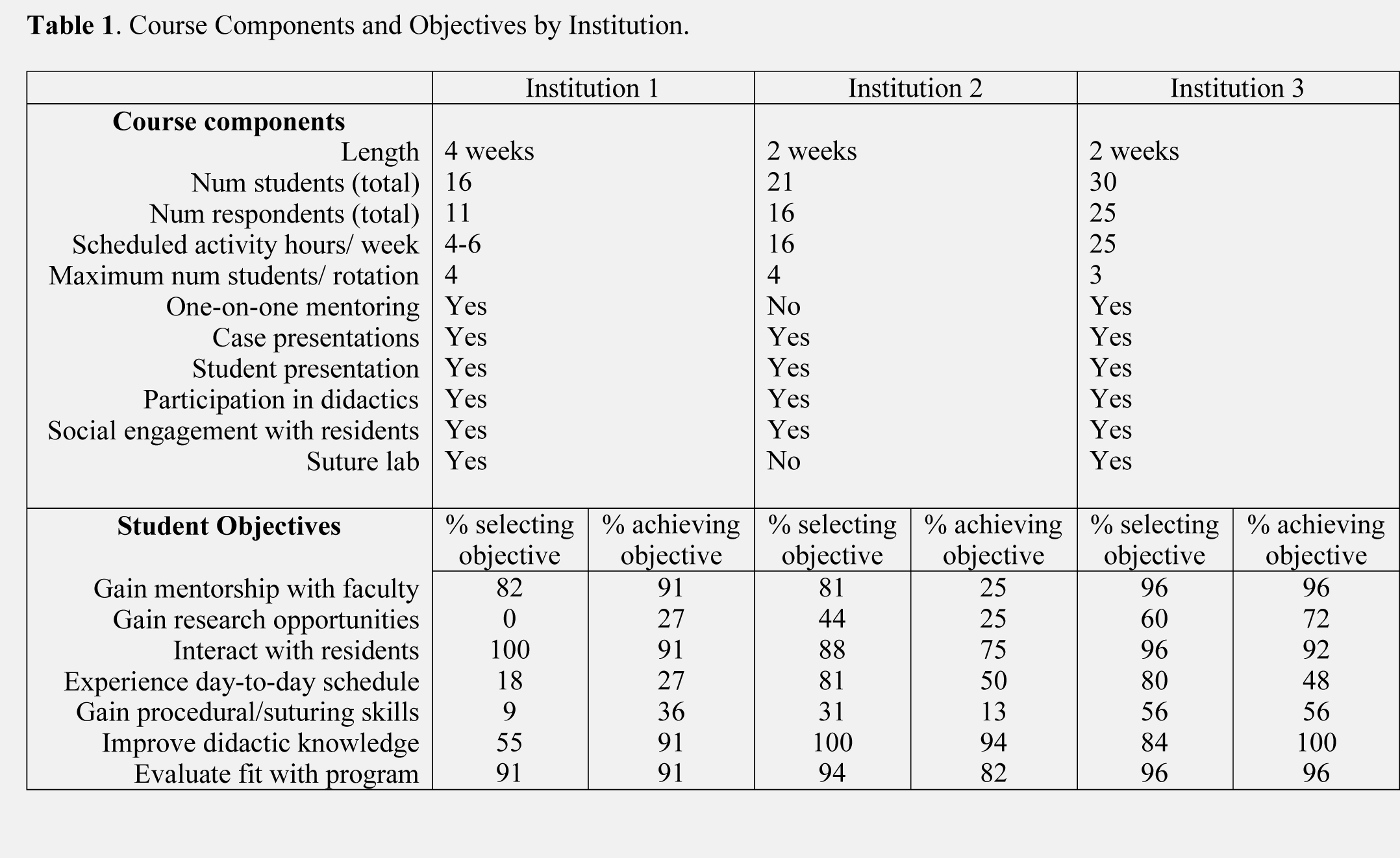

Background: Due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Council of Academic Plastic Surgery officially recommended halting all in-person student rotations and interviews for 2020. To offer an alternative for education and recruitment of prospective plastic surgery applicants, many institutions created virtual sub-internships. The purpose of this study is to analyze student goals for virtual sub-internships and assess how three institutions were able to meet these goals, identify areas of success, and give insight for improvement moving forward. Methods: Students participated in virtual sub-internships of 2 to 4 weeks duration at three institutions. Virtual sub-internships at each institution were independently developed and had both unique and shared components as outlined in Table 1. All students were administered the same pre sub-internship and post sub-internship survey via Qualtrics. Objectives were considered “met” if they ranked 4 or 5 on a Likert scale 1 (objective not met) to 5 (objective very well met). Responses were analyzed via Fisher’s exact test and t-testing. Result:s Fifty-two students completed both surveys (78% response rate). Sub-internships were most commonly advertised via Instagram, email, and word of mouth. The primary objectives of students pre rotation (Table 1) were to 1) interact with residents (94.2%), 2) evaluate their fit with the program (94.2%), 3) gain faculty mentorship (88.5%), and 4) improve didactic knowledge (82.7%). More than 73% of students endorsed having all primary objectives met. Sub-internships led to a significant improvement in considering the residents a strength of the program (p=0.011), and less often considering research opportunities (p=0.025) or geographic location (p=0.046) a weakness of the program. On average, students ranked programs 5% higher overall post sub-internship (p=0.024). While the majority of students perceived the virtual sub-internship as slightly less valuable (71.2%) than in-person sub-internships, all students reported that they would participate in a virtual sub-internship again. Conclusion: Student objectives can effectively be met using the virtual format for sub-internships while incurring less expenses and complying with pandemic restrictions. The virtual format is also effective in increasing the overall perception of a program and its residents. While students still prefer in-person sub-internships, increased exposure to research and mentorship opportunities has the potential to further improve subsequent virtual sub-internships. We strongly encourage residency training programs to continue offering virtual learning opportunities for medical students and consider tailoring their course components to program-specific goals.

Back to 2021 Abstracts